It was on the back of an opportunity to interview King Letsie III at his 51st birthday celebration last year – held at the royal palace in Maseru, the urban capital of the Kingdom of Lesotho – that I began an unexpected obsession with understanding the Basotho blanket.

There was no way to predict the path my preoccupation would take me on. Travelling from the “highest lowest point” of all the countries on the planet to the highest point in South Africa/Lesotho, I discovered the immense story of war and passion, heritage and modernity that is woven into the fibres of every authentic Basotho blanket.

The invitation to the king’s palace came through Tom Kritzinger, the passionate marketing director of Aranda Blankets – which has been manufacturing Basotho blankets since 1835 and is now housed in a factory the size of four soccer fields in the south of Johannesburg. I had been in conversation with Tom about an exhibition he was closely involved with at the time called Seanamarena: Kobo Tsa Morena. It was the first full-scale blanket show, on display at Oliewenhuis Art Museum in Bloemfontein. The exhibition displayed more than 40 unique blankets, some dating back to 1934, mounted and fully stretched out on the walls.

It was the first time I had seen them that way. By framing them on a wall, the exhibition unfolded the Basotho blanket from the bed and unwrapped it from the body to eloquently mount it for me to admire as an object in its own right. In that new context, the blankets were able to speak for themselves and tell the story of how intricately they were woven together with the history of Lesotho and its struggle for independence.

The exhibition began with a graphic leopard-print blanket named Nkoe (leopard), in 90%-wool panelled with the five red stripes, called wearing stripes, that mark an authentic Basotho blanket. The conservator at Oliewenhuis, Elmar du Plessis, told me Nkoe’s pattern was placed as the first object on display in order to recall the leopard skin karosses worn by King Moshoeshoe, the first monarch of Lesotho. The stripes started as a fault at the English looms and became a trademark from then on.

Oliewenhuis curator Ester le Roux told the crowd gathered at the exhibition opening: “The beginnings of the blanket culture can be traced back to 1823, when a French missionary presented a blanket to King Moshoeshoe I.”

Some of those in the audience are from Bloemfontein but many have crossed the border from neighbouring Lesotho to attend.

“He accepted this gift and draped it over his shoulders ‘a la poncho’, and so started a clothing revolution among the Basotho people. From that day onwards, animal-skin karosses started losing their status as the normal clothing to keep out the bitter cold of the mountains, and blankets soon became the stock in trade for the Basotho,” she said.

Le Roux explained that the name of the exhibition came from what was known as the “chief” of the blankets, Seanamarena.

“At the turn of the 20th century, Charles Stephens, who was known as Seanamarena, owned a trading store in Hlotse [Leribe], which was known locally by the same name as its owner.

Later, Charles Hendry Robertson bought the store and retained the name Seanamarena. He started importing Basotho blankets in his own special designs and colours.

As the years passed, Robertson’s designs became known as Seanamarena, after the name of the trading store, which was the only place where the blankets could be purchased.”

Since then, the range of blanket designs has evolved and they can be bought widely throughout Lesotho and South Africa – each of them forming part of a historical archive of the time they were made. Significant among them is a Badges of the Brave blanket honouring those who fought during World War 2, given as a gift to the British royal family on a visit to Lesotho, as well as a curious Batho ba Roma blanket made to commemorate Pope John Paul II’s visit to Lesotho in 1988.

Walking between the massive looms and spinning machines at the Aranda factory, Tom explained the process of designing a blanket. “Most of the time, people approach us. For the traditional blankets, people will come to us with rudimentary, simple designs and our in-house design team transfers those designs into our computer-aided design software, which then becomes a graphic image processed by the machines that weave the blankets. What a lot of people don’t know is that the blankets are a Jacquard weave, meaning the designs are woven into the blankets and not printed.”

Last year, for the king’s birthday, a young artist, Motsamai Moloko from Lesotho, designed the Rabosotho blanket. It was a plush burnt orange and yellow, with kaleidoscopic graphic depictions of traditional Lesotho hats. After seeing Moloko’s magnificent blanket, I had to see the festivities attached to its wearing. Tom arranged an invitation for me to the king’s party and I was left to select my first blanket. I went for a pink-and-brown Badges of the Brave blanket to protect me from the chill of the Mountain Kingdom where, in the middle of winter, temperatures can sink to below 20 degrees Celsius.

But it was not to be. Faced with lines out of the door at passport control and customs, a press registration that pretty much required my first-born child and the immense security protocol surrounding such monarchal meetings, my window of opportunity closed. I was left on a chair in the middle of the town square watching the royal cavalcade drive past, glimmers of blanket peeking out of the blackened Mercedes windows. All around me, crowds waved as the king passed, all of them wrapped in their blankets.

Defeated but ready to continue, I got back in my car and began the next leg of my blanket adventure – a five-hour journey to a little-known place in the middle of the Lesotho highlands called Semonkong.

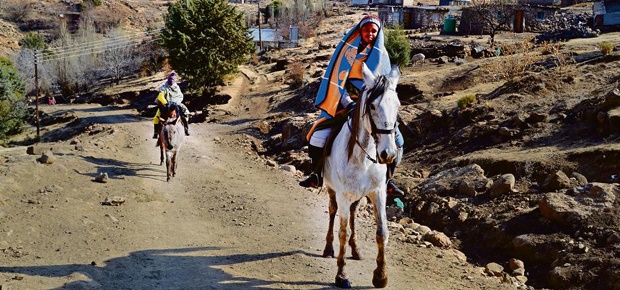

Once you get your breath back after taking in the sight of the winding heights on the brand-new overpass from Maseru, you come to a little village set in the valley of the lowest point in Lesotho (which is higher than the lowest point of any other country, making it the highest lowest point in the world). It’s the Maletsunyane Falls, from where Semonkong gets its name. It means place of smoke and describes the mist from the crashing waterfall. Semonkong is the only place in Lesotho to have its own regional blanket. Decorated with a graphic of the Maletsunyane Falls, it is the end point for anyone looking to undertake a blanket pilgrimage, and the people there know it. From the moment you enter the rugged country roads, you weave between towering horse riders, their blankets covering them entirely. They appear as sentinels, guards in blanket armour. Two of the horsemen took me on a horseback trip down to the waterfall, frozen seemingly in the middle of its fall. For an hour into the hills and valleys, I encountered villages built around enormous flocks of sheep.

It was their precious mountain wool, collected by a sophisticated community of local farmers and distributors, that had ended up in Joburg to finally make the blankets we were wrapped in.

The walk through this region was almost constantly on the edge of a cliff, our horses swaying and tripping with the howling force of the wind. The icy climes were not play-around Joburg or Cape Town cold ... they were proper Lesotho freezing.

There was no escaping it without our blankets wrapped around us. The cold was an object lesson of why the Basotho treasure their blankets for much more than just the way they look – they are a very real, functional protection against the glacial bite of the wind.

Back at the lodge, I was again reminded of another reason why there was so much to the blanket.

Atop a hill near the lodge, a mother was tying a blanket around her child’s shoulders. It wasn’t simply a smaller blanket but actually a piece of her own blanket she had cut and passed on to him. Next to his mother, wearing a piece of her blanket, this young man wore the history of his country. It was passed on, from one generation to the next, in something as simple as cloth.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners