A week or so leading up to Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi's first solo exhibition, the Stevenson’s Johannesburg Gallery announced that they'd be foregoing the usual opening night.

The Covid-19 virus had begun its spread throughout South Africa. Since then, the global pandemic has cast a shadow over this moment — the show opened a day before South Africa's 21-day lockdown and will close on what is currently the last day of the lockdown - 30 April 2020 - after the lockdown was extended by two additional weeks.

"The timing has had a few different effects," says Nkosi. "Firstly, I was finishing off the paintings at a time when the scale and severity of the pandemic were really coming into view, day by day. So I was going to my studio every day in this atmosphere that was getting more and more fraught. Then a 'lockdown' became something people were talking about. Which was surreal but suddenly this very real possibility. So the question was: is this going to happen before or after the show opens? It was a very strange way to finish up what had been a very long and patient process of thinking and planning and painting."

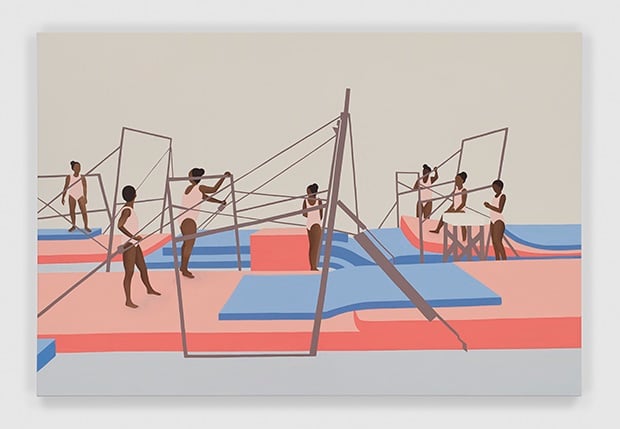

In a way, Gymnasium, which consists of 8 paintings and one video, is still slow work. It finds its legs in a painting completed by Nkosi in 2012 while examining the architectural inheritance of spatial apartheid. Having happened upon an image of two white gymnasts, she asked herself what it would mean for the image if the gymnasts were black?

WATCH: Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi walks us through Gymnasium

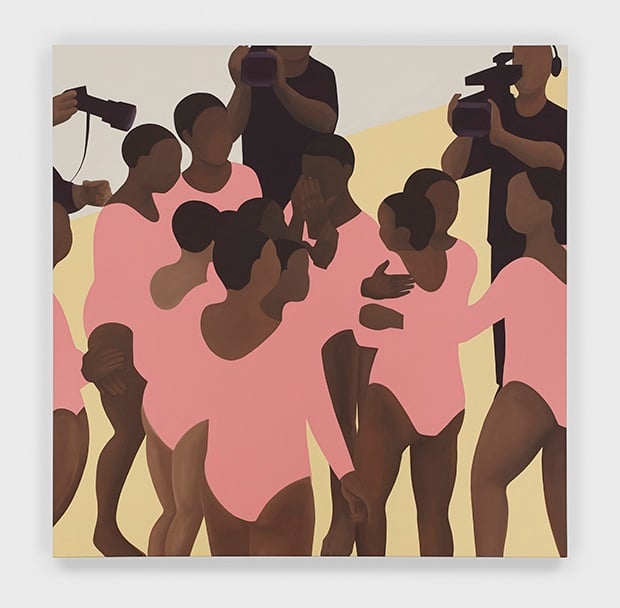

Gymnastics, much like any competitive sport, invites onlookers — everyone from fans, commentators and the sporting codes governing channels are encouraged to give opinion, to judge. But to be a black girl or woman striving for individual excellence invites its own attention. Suddenly, it is not your prowess that is under scrutiny but your very body. Its blackness. What does it mean to present oneself for evaluation? To continually be aware of the scorecard against which you are rated, the parameters of which are defined externally? What does it mean to be looked at?

For black women athletes, think Serena Williams, Caster Semenya, Simone Biles or French Figure Skater Surya Bonaly, it means accepting that rules take on expanded dimensions when you are good and black. Your performance is no longer a cause for celebration but rather a cause for suspicion. "...each one of [these women] has had this other experience parallel to their phenomenal athletic careers, careers in which they have dominated their competitors, sometimes rewriting the rules of what is possible," explains Nkosi.

“And this parallel experience has been one of great vulnerability, where they have been under extreme, often violent pressure; where they have been constantly on the receiving end of all kinds of insults and accusations, explicit and implicit, from outside and inside their sports. The greater their sporting achievement, the fiercer these attacks have been. Their stories really are important lessons in the fundamental presence of racism in the world. Even at the peak of sporting achievement and fame, there is no escape from racism and the ways in which it seeks to bring us down," says Nkosi.

And in an act, often described as rebellion or aggression, but which always just looks like agency, black women athletes push themselves to do the impossible: Bolany performs a one-bladed backflip at the 1998 Winter Olympics; Simone Biles flies at the 2019 U.S. Gymnastics Championships. Rules and criticism be damned.

The video, Suspension, opens on a shot of a young black woman in the spandex uniform of her home team, USA. The three letters sit in white across her chest. Her one arm is bent above her, out at the side and the other is bent in front of her frame, hiding her face. From above the crook of her elbow we see the brown of her forehead, the brown of her coiled afro. In the frames that follow, more women, either at the end of a routine or a beginning. It is difficult to tell. It appears the gymnasts are on the precipice of something.

There’s a tension here but it’s quiet, almost ritualistic. Some of them mutter to themselves; others just breathe. Chests rise and fall. Lips are pursed - controlled breathing. Lips pouting to the side as someone eats the inside of their cheeks. Almost two minutes into the video, the viewer begins to wonder if they will ever take off and soar; wonder whether the whole point of the video is this moment of uncertainty. Powdered hands and all. There’s no denying that there’s something coming and each athlete is bargaining, either with her training, God or gravity itself to carry her to perfection or greatness. Who can say which?

Watch: Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi's Supension here

Gymnasium (2020) is open at Stevenson Gallery until 30 April and will remain available online.

Nomali Minenhle Cele is a writer from Soweto.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners