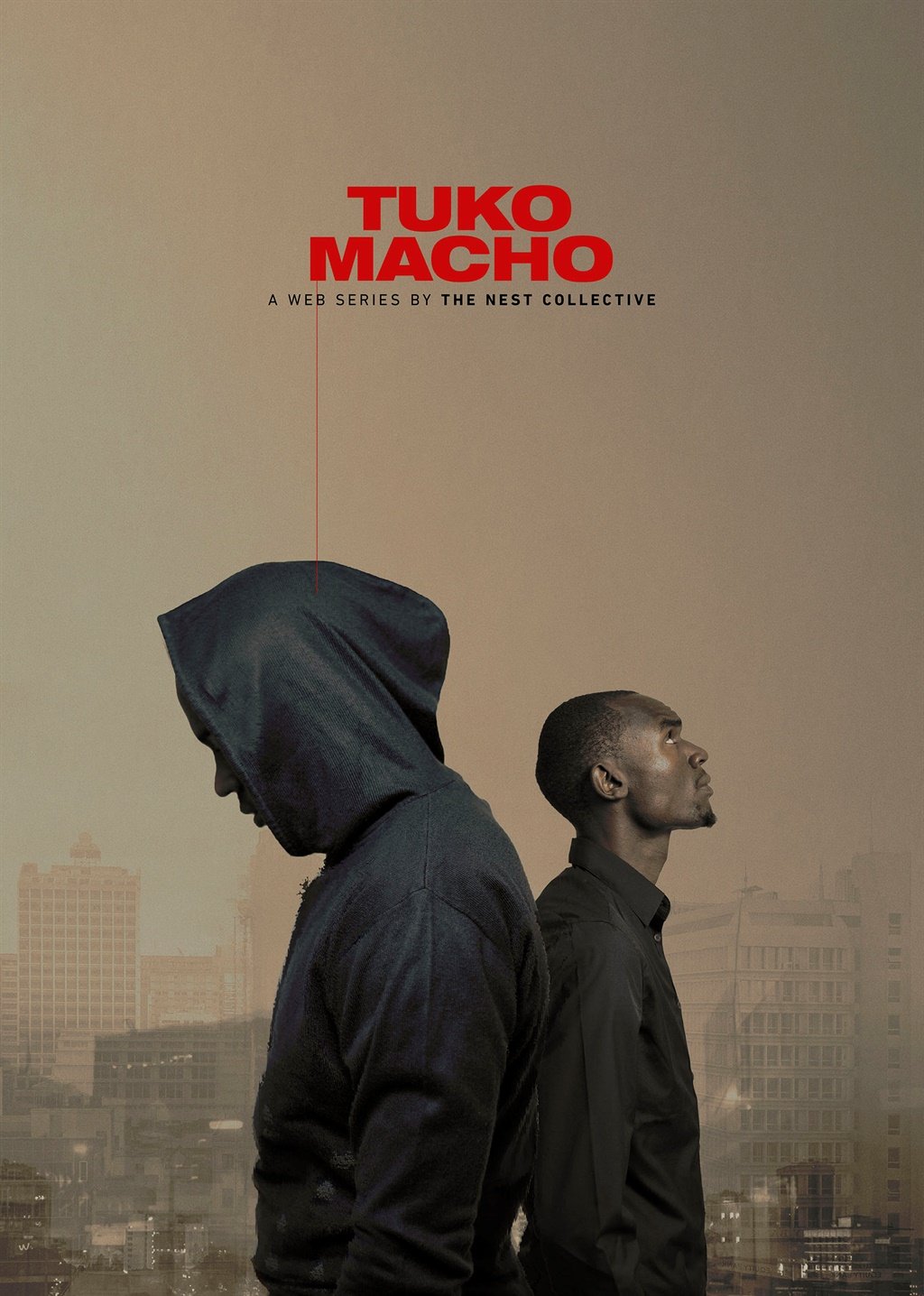

“It’s not me who will kill you. It’s the people. The people will kill you”, says Biko the vigilante commander to Charlo, his prisoner, in the first episode of Kenyan web series Tuko Macho. Created by Nairobi-based art collective The Nest in 2016, the series follows an underground squad that kidnaps criminals and prosecutes them on live stream, with the public playing jury via online voting. If the majority votes not guilty, the squad—whose name Tuko Macho means “We Are Watching”—releases them. If guilty, they are executed live on camera, their corpse dumped outside a police station in a macabre middle finger to dysfunctional law enforcement bodies.

Charlo, the squad’s first target, is a carjacker whose civility strikes a chilling contrast to the gun he holds against his victim’s neck. His nonchalance hints at the violence to which Charlo himself has been subjected, as a child raised on the deprived edges of urban dystopia. “By the time Charlo grows up he’s casual in the return of that violence,” says Jim Chuchu, director and co-writer of the series.

He continues:

In captivity, Charlo tells Biko about his mother, a cleaner who spent her life doing backbreaking labour for rich people who got richer and richer while she barely scraped by. Unwilling to struggle as she did in an unjust economy, Charlo turned to crime. “Every day this city produces more people like me”, he says. And yet he does not expect this city, these people, to spare him from the pressures of their own survival. “Will you kill me?” he asks, and when Biko explains who will decide his fate, Charlo scoffs. “The people? I’m out of luck then. Of course they’ll vote for me to die.”

If online clicks wielded such lethal power in real life, many mansions might be littered with bodies as social media amplifies a growing appetite to “eat the rich”—especially in the global turmoil of 2020, when Tuko Macho feels more relevant than ever. From looting of food shops in Italy, demonstrations against police brutality in Kenya, and protests against systemic racism in the US that have spread across the world, there is a rising sense of pushback against oppressive systems.

The concept of Tuko Macho was in part inspired by these systems, and the people who run them through abuse of state, corporate or religious resources to further personal agendas. “Those are the supervillains to me”, says Chuchu. “They wear suits, they speak in church.”

In a 2017 conversation with Nairobi Side Hustle, he elaborated: “they are above the law in a way that’s depressing. It’s almost like fiction, how much people can get away with here.” Against this factual backdrop Tuko Macho presents an imagined, but not implausible, vigilante reaction to a range of villains—with the squad’s other targets including a pastor, city councilman, taxi driver and cabinet minister. By making an example of these few, Biko reasons, they can deter criminals and transform society.

The public response, deftly conveyed through fictional media footage woven throughout the series, is polarized. “If the government can’t do its job, we will!” declares one gleeful citizen after Charlo is executed. Human rights activists condemn vigilantism and urge respect for official institutions, but in light of history their urgings ring hollow. “We have heard all this before,” exclaims a TV commentator. “We can come up with a list of institutions that we need to strengthen, replace or refresh, but the root cause of the problems we have in this country is a generation who don’t even believe in the idea of justice”. Where institutions have failed, Tuko Macho delivers—and your vote counts.

The series was released in weekly instalments on Facebook and real-life viewers were invited to vote on each criminal, with the majority verdict determining what would happen in the next episode. While The Nest did all filming in advance and shot extra scenes so editing could swing whichever way viewers voted, Chuchu recalls that all their predictions were fulfilled: revealing a “suppressed desire for vengeance in the public” that blurred the line between real and imagined worlds.

On screen, the fictional voters of Tuko Macho grow steadily in number, ignoring official warnings against participating in the vigilante trials. Eventually the police threaten criminal action against anyone who visits the squad’s website, but even then, a lack of faith in government institutions prevails. “So now they want to arrest me because I voted?” smirks a woman being interviewed on the street. “How will they prove it when they don’t even have internet?”

The voting process, while powering Tuko Macho, also connects with a larger conversation on democracy. Flashbacks reveal Biko’s past encounter with vote rigging, and questions around the legitimacy of elections are layered with subtext on the violence that underpins these murky hallmarks of democracy. The vigilantes offer a more clear-cut politics: the power to directly elect one form of violence over another.

In that sense their brand of democracy is like many across the world, where regardless of ballot results, violence remains embedded in the systems that govern our lives. Sometimes this looks like a gangster’s gun or policeman’s knee to the neck; sometimes it looks like a worker who, despite decades of gruelling labour, cannot escape the clench of poverty. “We teach children about civics and democracy, but we don’t teach them about its fictions, which I find strange”, says Chuchu. “We don’t equip ourselves for the realities.”

In a world where these realities are increasingly polarized and people now have unprecedented power to connect and cross-pollinate their outrage, Chuchu predicts that radical resistance will gain momentum over the “architecture of compromise” on which post-colonial states were built. So resonant is Tuko Macho with some worldviews that when The Nest screened it in Mathare, an informal settlement of Nairobi, viewers thought it was a documentary. “In the same way that people are increasingly attacked online for being moderate or inconsistent with their values,” says Chuchu, “I think that kind of policing will spread to communities. There is no room for moderation in this world that we are going into.”

Biko exemplifies this, taking extreme measures to avoid complicity with injustice. “I don’t think it was fair what they did, and I don’t like that I was involved”, he says in a flashback about his decision to expose election fraud, which wins him momentary praise then sparks brutal backlash that ultimately leads him to take justice into his own hands. But justice, as he finds out, is always messy, and sometimes entangled with other injustices. Tuko Macho is unflinching in its portrayal of this complexity through incisive writing, stark visuals and understated but powerful performances.

Still, there is something like hope in the quiet spaces. There is the safehouse where a steely woman shelters marginalized young people and nurses Biko back from the grave. There is the label-defying relationship between a sex worker and a police detective, which creates oases of tenderness. But in the end, while Tuko Macho allows its characters to dream, it does not offer any escapes from reality. “We are children of dystopia”, Chuchu says. The viewer is left with uneasy questions that stretch beyond the screen into a world where fact is stranger than fiction, democracy as elusive as justice, systemic violence cloaked in the nonchalance of Charlo the carjacker.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners