- Lunga Ntila works in the tradition of digital collage and self-portraiture.

- Historically, collage has functioned as a strategy for the rescue or re-writing of Black photographic violence.

- In Ntila's work, the collages not only order an image from its disjuncted parts, the collages also obfuscate, denying easy interpretations.

“Now once I feel myself observed by the lens, everything changes: I constitute myself in the process of posing, I instantaneously make another body for myself, I transform myself in advance into an image.”- Roland Barthes

“It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one's self through the eyes of others, of measuring one's soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.” - WEB Du Bois

Since its origin, photography has been thought of - in both superstition and theory - as a medium with the strange capacity to play beyond the bounds delimited by material life. Susan Sontag once described the taking of a photo as a kind of participation “in another person’s (or thing’s) mortality, vulnerability, mutability...”

According to her, the kind of killing a camera is capable of is a “soft murder”, where a likeness is "captured", stilled in time, and infinitely reproducible through slide, negative, or digital file of uniquely arranged pixels. Simultaneously intensifying the impossibility of temporal return, and the gradual loss of authentic memory, photographed portraits are bodies of other time, dead but not gone - ghosts we’ve grown comfortable living with, collecting and exhibiting. Ghosts for looking at.

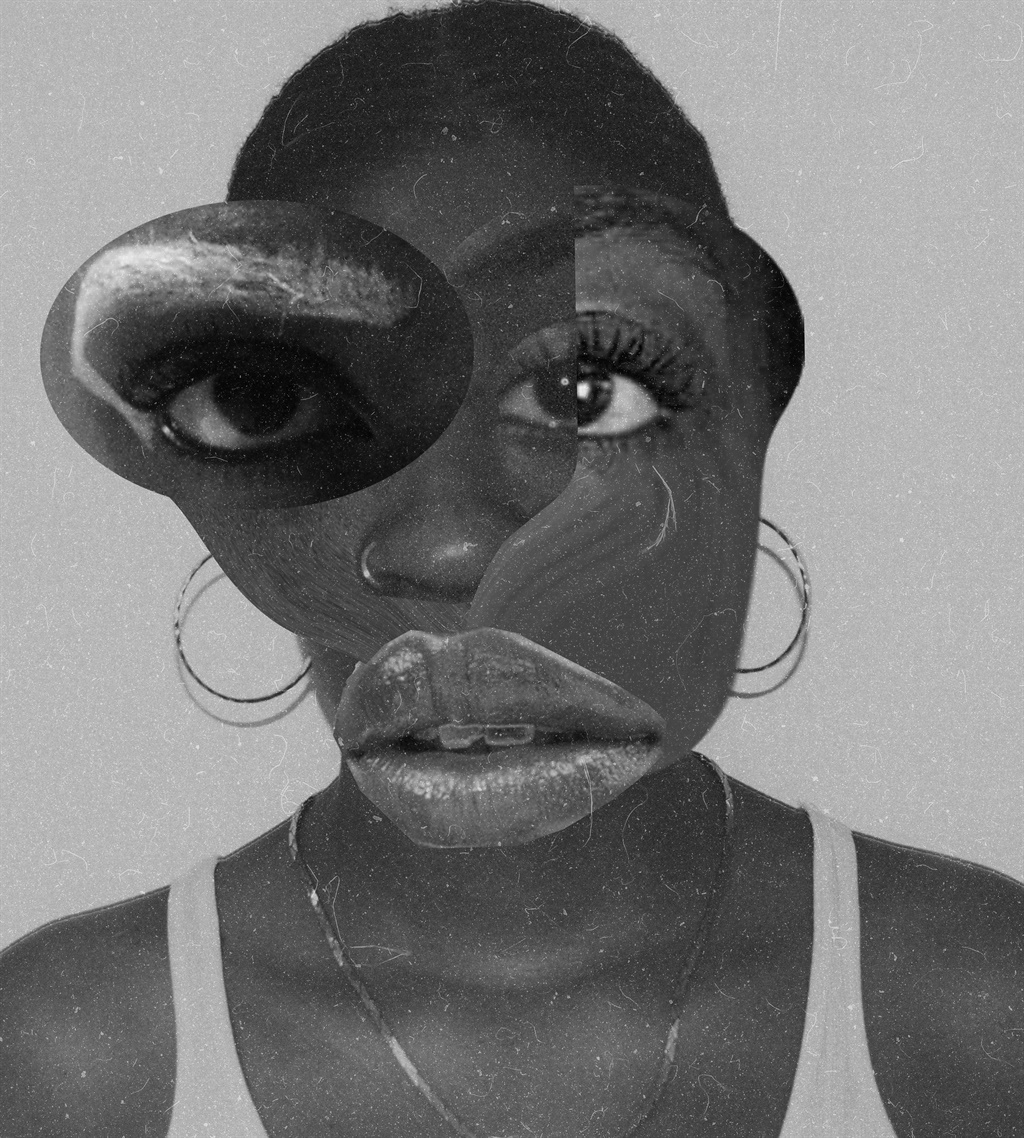

Lunga Ntila then, is both ghost and looker, working in the tradition of self-portraiture as well as in digital collage, a process in which the captured image is undone and then strangely reconstituted. Through collage, the practitioner’s originals are able to meet and find conversation together, as their pixels are cut, stretched, and layered into mutant digital bodies of semi-fictional characters, all based in the parallel universes of a single face. An eye from one day, maybe, meets another three from a week later and these are placed, just off, beside the lips of a different time and last month’s nose. Ntila’s extended photographic involvement, beyond providing face, as director, photographer and post-production technician, burdens her portraits with an intensified subjectivity, a deep and immediate presence rarely associated with the medium of collage.

But beyond this, her permeating presence opens some reflective space as to the question of photographic death and subjectivity (life), in regards to a sitter already formed historically through ghostlike terms, as ontologically negated, unmade, or indeed, socially dead. For all the white talk of photography as a death producing mechanism, there is a wealth of Black radical thought regarding the entirety of the racialised world state as a series of mechanisms (photography included), that similarly render Black people as body-objects, vulnerable to unthinkable violence.

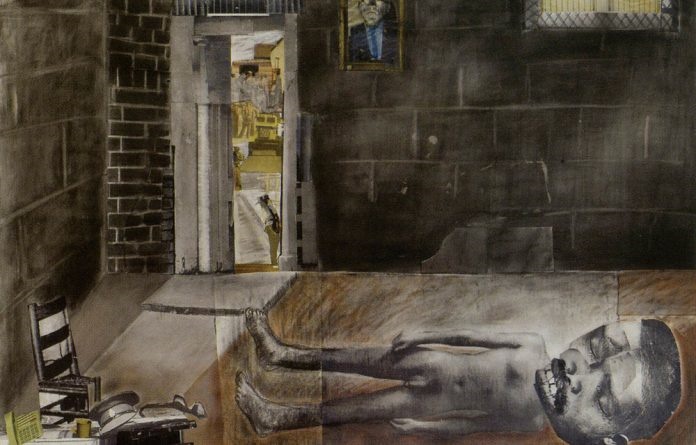

It is of no surprise that collage functions historically as a strategy for the rescue or re-writing of Black photographic violence. I can’t help but recall Sam Nhlengethwa’s famous 1991 work, It left him cold - the death of Steve Biko, a collage and painting work whose fierce brutality is made present most potently through the quietened, clumsily pieced together corpse of Steve Biko. The silent body offers little materially, but in the awkwardness of its embodiment, seems to refer somewhere beyond itself, to something that is unholdable here (this may be the work of a good memorial). Somehow, the photographic over-presence of body, combined with its breakdown through collage, seem an aptly confused response to Black mourning, an existential predicament of absence, which begins long before one is gone.

In the text for Ukuzilanda, Ntila’s first solo show, held at BKhz in Braamfontein in 2019, Zaza Hlalethwa writes that Ntila’s collage work is strategic in its concealment of the subject’s real face. Hlalethwa explains that in this instance, collage operates as a protective and even healing mechanism, shielding the sitter from the “unwanted gaze”. So while the works are visually conventional in many ways, from their straight, contained compositions to their neatly framed display, they are involved in a rather tortured, circular process, back and forth between violent photographic capture, and then redemptive collage-based care, the warping of narrative, the unmaking of truth.

For as Hlalethwa reminds us, institutional ‘truths’, like phrenology, or scientific racism, have historically served as justifications for the genociding, colonising and enslaving of Black people (truth should be avoided at all costs). In my view, under these circumstances, concealment alone can never be entirely healing, but, as a changeable strategy of self and collective remaking, can act more as a mobile tactic in the spiritual survival of another day. This is to say that the ethic of ongoing improvisation, the constant attempt at caring for the Black portrait under duress of violent consumption, lends Ntila’s deceitfully stilled works the character of careful motion and tactical prowess. Collage offers redaction, and redaction, in the right hands, may grant space for planning - opaque and surprising action, in denial of the taxonomic truth.

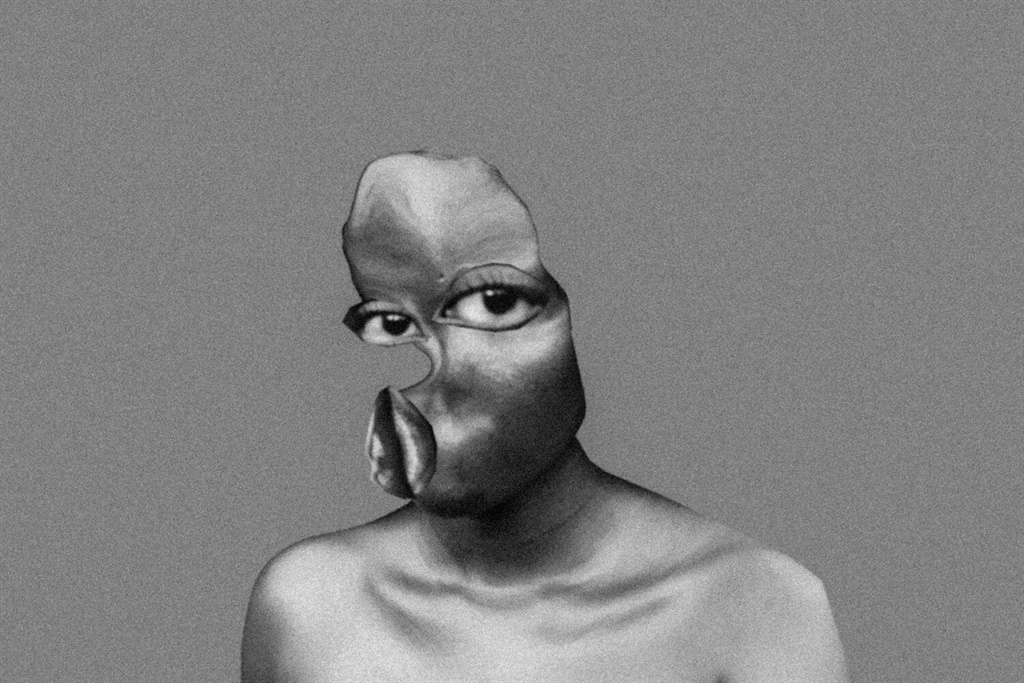

Recent images from Ntila’s instagram feed immediately recall Minette Vari’s warped multiples in Alien, from 1998. Although I remain hostile to the brand of white liberal takeover that marks this era of South African art, I reluctantly admit that Alien is a weird and wonderful piece of video work that visually exceeds its intent. Against an ironic, minimal and grayscaled "South African" landscape, including, at different times, a Mandela silhouette, some or other mask, and even a lion, Vari, naked and in multiple distortions, is unfixed, shrinking and stretching, a misplaced, if fluid and stumbling oddity of some vintage white #AfricanFuture. The short video work locates something hypnotic in the extra-terrestrial, a queer comfort in resolute elasticity, and a bendy proposal for managing life, in body.

For visual distortion always feels like an expression of discomfort, in recognition of the repeatedly obscure, graceless attempt to fit soul and personality into ever-degrading body of bone and tissue (connective, protective, nervous, and so on). The habit of collage – nervous - or the undress of the photographic, has to tell us something about the body’s ultimately clumsy fit. And in their increasingly abstracted black and white curves of glowing skin and peaking digits, billowing stretches and smooth folds, Ntila’s newer collage work builds precisely on this futile (but inevitable) tradition of frustrating the limits of flesh.

Such frustrations are temporal: By mixing versions of the same (but different) face and body, flattening multiple timestamps into a single abstracted pixel field, Ntila’s images could be understood as kinds of metaphysical memorials, pushing the body of alternate pasts into simultaneous existence. They could be artefacts, for their seeming allusion to some event or history outside of their composition. The portraits act.

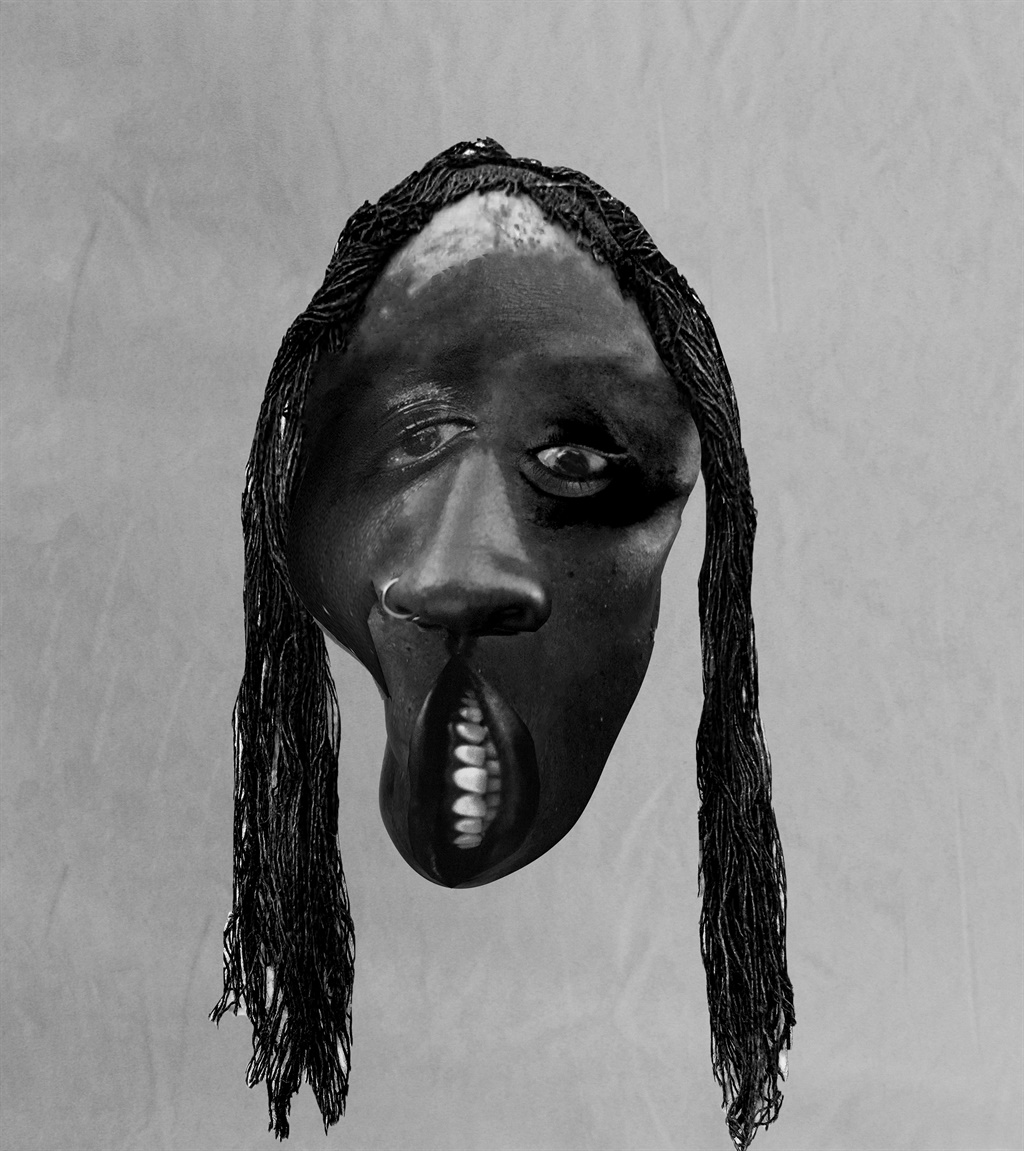

Starkly centered in a plain field, Mask immediately references something of colonial archivist tendencies that prioritise the isolation of (stolen) objects marked as ‘cultural’, thus Black, thus illegible, in order to categorise them. The taxonomic impulse is a panicked one, where the typing of things and people takes place necessarily outside of the context in which they might form flexible relation. And herein is the establishment of white authorship - a knowledge style of authority without relation. That Ntila takes on the colonial visual strategy, and that the mask, the artefact, or the portrait is made in her own (distorted) likeness, somewhat confuses and elaborates on the work of power in assembling representations of Black gendered or queered bodies, most vulnerable to dangerous looks, and looks as prequel to danger. Put another way, in Mask, the objectified body voluntarily makes herself object/ artefact, and in this transformation, eerily seems to gain some other kind of flexible subjectivity.

The most striking mask, for me, includes a smiling mouth turned ninety degrees to the left (of where most mouths appear on faces), one upside-down, and one downward-leaning eye, all surrounding the centered nose, and embedded in a long, resolutely asymmetrical face that is framed on either side by fine braids reaching to the image’s lowest frame. Eyebrow-less, and oddly dented in places, the worn countenance is stilled in some expression, unreadable, and exceeding human cognitive capacity for instinctual facial expression recognition. A smiling mouth, we learn here, is not read in its original joy when rotated upwards into new congress with nose and eyes, and thus, new congress with the world.

With capture, redaction, distortion, and a series of "new congresses", Lunga Ntila enters an old conversation on the problem of the (Black) body, the problem of its likeness, and the spiritual struggle away from the politics in which it continues to be reproduced.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners